Breaking into new markets and winning major government contracts can be a daunting task for even the largest corporations, doubly so in emerging markets that are in political transition or have gone through a recent major upheaval.

In the face of such challenges, some companies may decide that engaging in illegal activities, often taking the form of bribes to foreign government officials, is an acceptable cost of doing business. When caught, hefty fines and settlements serve as both punishment for and deterrent against corruption practices.

But even before sanctions are levied, an investigation or ongoing lawsuit will raise red flags in any thorough due diligence check. In the most egregious cases, allegations of bribery can haunt a company’s reputation for decades.

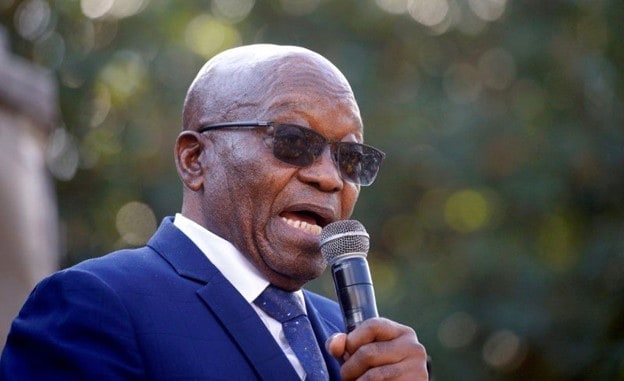

One such case in the news in recent months is a lawsuit in South Africa, in which French defense group Thales is accused of racketeering, corruption, and money laundering. The other defendant in that trial is former South African President Jacob Zuma, who faces charges on 16 counts of racketeering, corruption, fraud, tax evasion, and money laundering.

Zuma is alleged to have accepted more than 700 bribes over a period of 10 years, including cash payments from Thales. The accusations cover the time when Zuma was deputy president of South Africa from 1999 to 2005.

The charges relate to the 1999 military equipment deal signed by South Africa with a group of European defense companies, worth 30 billion rands, or nearly $5 billion at the exchange rate at the time. Zuma is accused of accepting bribes totaling 4 million rands from Thales in exchange for shielding the company from the investigation.

Two Thales subsidiaries, Thint Holding (Southern Africa) and Thint, were charged with corruption in 2005, but the only people convicted were the African National Congress (ANC) chief parliamentary whip at the time, Tony Yengeni, and financial adviser Schabir Shaik.

Yengeni went to prison in 2006 and served five months of his four-year sentence, while Shaik, who was found guilty of soliciting a bribe from Thint on behalf of Zuma, was released on medical parole in 2009, four years into his 15-year sentence.

Shortly before Zuma was elected president of South Africa in 2009, charges against him were dropped, only for the South African Supreme Court to rule in 2018 that they should be reinstated. Thales sued to have the charges against the company dropped, but the Kwazulu-Natal High Court in Pietermaritzburg ruled in January 2021 to dismiss its application.

For the record, Thales has said it had no knowledge of any transgressions by any of its employees in relation to the award of the contracts. On May 26, 2021, its representative pleaded not guilty to the racketeering, corruption, and money laundering charges against the company.

Thales is not the only company involved in the 1999 South African arms deal to face investigation. The Serious Fraud Office in the UK investigated British defense firm BAE Systems over several contracts and reached a 30 million pounds plea settlement in 2010, without pursuing a criminal case concerning the South Africa deal.

The same year, BAE Systems also pleaded guilty and agreed to pay a $400 million criminal fine following a US Department of Justice investigation. That settlement did not specifically mention the South Africa deal.

Other recent corruption investigations resulted in even larger fines. Airbus agreed in January 2020 to pay $4 billion in fines as part of its settlement with authorities in France, the UK, and the US, after being investigated for allegedly using intermediaries to bribe public officials in numerous countries to buy its planes and satellites.

The trial against Zuma and Thales in South Africa is still in its early stages and has been repeatedly postponed—most recently, to September, due to his failing health. He was jailed last month on a contempt of court charge relating to a separate corruption investigation.

Thales may or may not be found guilty, and it remains to be seen what financial penalties the company might face but the shadow of suspicion over the company may linger even longer.

About Kreller Group

The Kreller Companies were founded in 1988 by a former D&B national account manager who envisioned a straight forward and cost-effective way to conduct business investigations and share results with clients. Today the Kreller Companies are comprised of Kreller Group, Kreller Credit and Kreller Consulting.

Want to discuss how our expertise can help? Click here.